Three Classic Chinese Games to Help You Learn Mandarin

Curious about classic Chinese games? Check the article for details, history and instructions!

Games have been a central part of Chinese culture for thousands of years, and a working knowledge of how to play will provide you with an instant conversation starter. They're also a superb way of learning and practicing Mandarin. Playing these games can encourage you to think in Chinese, sharpen your response time, solidify your grasp of numbers and terms and most importantly, befriend people with whom you can practice speaking Mandarin regularly.

Mahjong - 麻将

Mahjong - 麻将 (pronounced as májiàng) is the many-headed hydra of Chinese tile games. Master one style and another pops up with renewed vehemence. Styles differ from region to region, with forms including Old Hong Kong, Japanese, Three Player and Singaporean. This article will focus on 四川麻将 - Sìchuān Májiàng, namely because it's the simplest (and thus easiest to explain) form of the game.

The name 麻将 - májiàng comes from the word 麻雀 - máquè, which translates as sparrow. Fable goes that the elders and nobility who first played the game felt the sound of májiàng tiles (麻将牌 - májiàngpái) clacking together was redolent of the chatter and titter of busy sparrows. Despite romantic notions of Confucious playing 麻将 - májiàng in the early BC, the game as recognised today wasn't documented until the 19th century. Several predecessors such as Madiao, Ya Pei and Mo He Pai were popular in the centuries before 麻将 - májiàng became widely known, and different elements of these games have been plucked from these ancient games to form the rules of 麻将 - májiàng as it is known today. It should be mentioned that 麻将 - májiàng is a game that depends heavily interaction between players during gameplay. If you're harbouring a bit of skill-based reluctance about jumping into a game, polish your listening skills before heading out and playing for real.

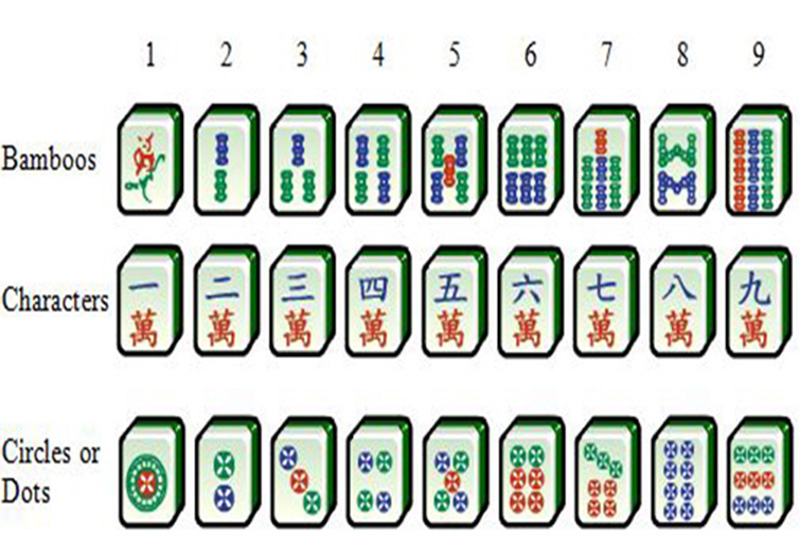

The three types of tiles 麻将牌 - májiàngpái can be seen above. The three types are:

Bamboo - 条 - tiáo

Characters - 万 - wàn

Dots - 筒 - tǒng

There are a total of 108 tiles in the game, four of each tile. To get going you need four people, a flat surface and a sizeable dose of wherewithal.

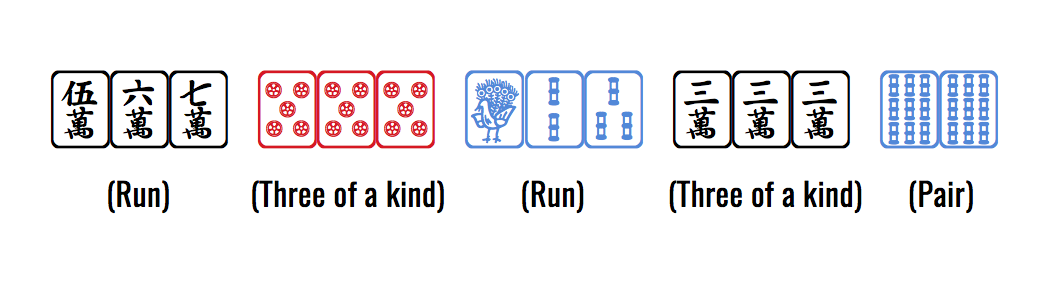

麻将 - Májiàng is very similar to the card game rummy, in which you have to complete a hand by making sets of runs, doubles or trebles.

The fundamentals of the game are simple. Each player has 13 tiles (牌 - pái), and they take it in turn to take a tile (牌 - pái) from the middle of the table in an effort to create a set of 14 tiles (牌 - pái) comprised of four sets of three and one set of two. However, the game contains myriad intricacies and quirks, especially when gambling is involved. For a more detailed account, see this great article.

Go - 围棋

The oldest continuously played board game ever according to some reports, Go (围棋 - wéiqí) is a game of simple rules but complex gameplay. Double derivation in the etymology here - the term Go comes from the Japanese igo, which is the Japanese reading of 围棋. 围棋 - wéiqí translates as game of encircling, and in modern Mandarin 围 - wéi can be seen in words such as 包围 - bāowéi (surround),堤围 - dīwéi (embankment) and 周围 - zhōuwéi (around, about).

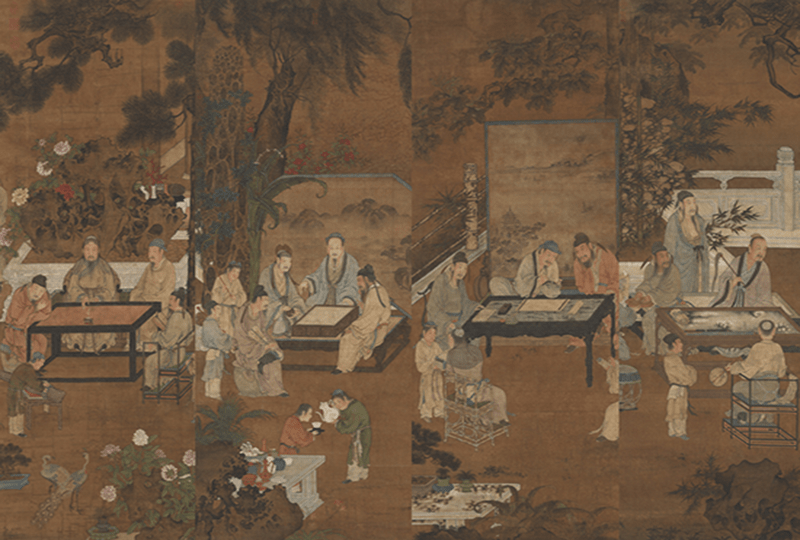

围棋 - Wéiqí was first mentioned in the 左傳 - zuǒchuán, a narrative history of ancient Chinese culture, and also appears in the writings of Confucious (孔子 - Kǒngzǐ) and Mencius (孟子 - Mèngzǐ). Many theories abound regarding the original purpose for the invention of 围棋 - wéiqí, though the most plausible hypothesis is that it has roots in the military practice of Chinese tribes and warlords, who would use small stones and pebbles when plotting raids and skirmishes. From these martial origins 围棋 - wéiqí was quickly adopted by the Chinese gentry and intelligentsia, to the extent that it became recognised as one the four scholarly arts (四藝 - sì yì) , along with the 古琴 - gǔqín (a stringed instrument), 書 - shū (Chinese calligraphy) and 畫 - huà (Chinese painting). From here the game spread through Asia, most notably Japan and Korea.

To play 围棋 - wéiqí a board (most commonly a 19x19 board, though smaller version are available) and 361 stones (180 white, 180 black) are all that is required. The essence of the game, as the character 围 - wéi suggests, is based on surrounding an opponent's stone. If a stone is surronded then then that stone is then captured, which would then be counted at the end of the game to decide the victor. There are several other laws and factors to dice with; see this page for more in-depth deets. This site offers interactive 围棋 - wéiqí training, or if you simply want to hone your 围棋 - wéiqí skills drop into this site and throw down with other players online.

Chinese Chess - 象棋

Chinese chess, known in Chinese as 象棋 - xiàngqí, is another ancient game originally played by the Chinese nobility. First mentioned as early as 100BC in a collection of stories called 说苑 - shuō yuàn, 象棋 - xiàngqí was a favourite of the warlord Lord Mengchang (孟尝君 - Mèngcháng Jūn). There is some debate over the origin of the name, as the character 象 - xiàng previously conveyed the several meanings. As a result, it is thought the 象棋 - xiàngqí could mean 'Elephant Game', 'Figure Game' or 'Constellation Game'. The modern meaning of the character 象 - xiàng is elephant however, and thus 'Elephant Game' is now the most commonly used title.

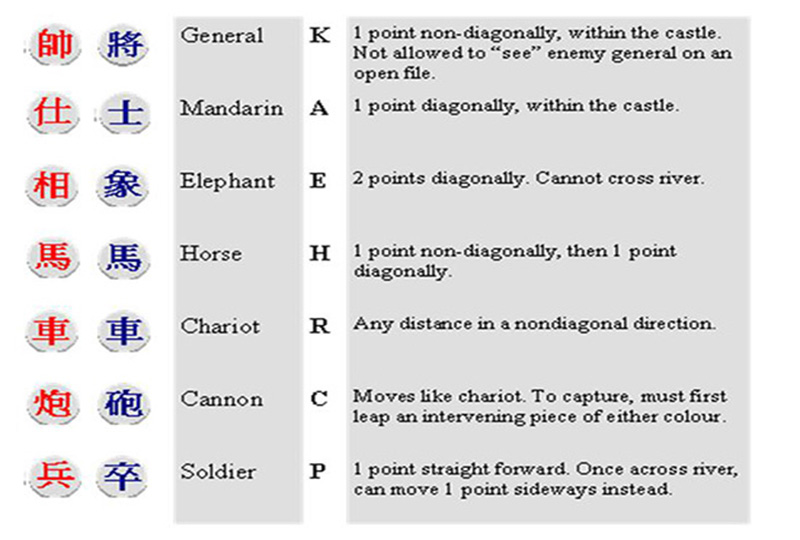

The game itself is very similar to the form of chess played outside of China. There are two players (black and in this case, red) and each has 16 pieces, with each piece being able to move and act in different ways. Each piece has a red side and a black side, and though both sides have the same function, they use different characters to describe the same word. Most 象棋 - xiàngqí sets use Traditional Chinese Characters (it is thought that the Traditional script is more comely and ornate) to denote which piece is which. It might be salient to brush up on your Mandarin vocabulary before striding out into the 象棋 - xiàngqí arena. If however, you feel ready and able, here are the different pieces, meanings and functions:

Generals

Black side - The General 將 (trad.) / 将 (simp.) - jiàng

Red side - The Marshall 帥 (trad.) / 帅 (simp.) - shuài

Advisors

Black side - Scholar, Officer, Guardian 士 (same in trad. and simp.) - shì

Red side - Scholar, Officer, Guardian 仕 (same in trad. and simp.) - shì

Elephants

Black side - Elephant 象 (same in trad. and simp.) - xiàng

Red side - Minister 相 (same in trad. and simp.) - xiàng

Horses

Black side - Horse 馬 (trad.) / 马 (simp.) - mǎ

Red side - Horse 傌 (trad.) / 马 (simp.) - mǎ

Chariot

Black side - Chariot, Car 車 (trad.) / 车 (simp.) - jū

Red side - Chariot, Car 俥 (trad.) / 车 (simp.) - jū

^(车 is normally pronounced chē but not when playing Chinese chess)

Cannon

Black side - Catapult 砲 (same in trad. and simp.) - pào

Red side - Cannon 炮 (same in trad. and simp.) - pào

Soldier

Black side - Pawn or Private 卒 (same in trad. and simp.) - zú

Red side - Soldier 兵 (same in trad. and simp.) - bīng

As shown above, the movements and abilities of each piece exhibit a striking resemblance to chess, and the object of the game is similar to chess: to win the game you must capture the opponent's general. If your opponent is unable to stop you from doing this, then the game ends in checkmate, known as 将死 - jiàng sǐ (dead general). Unlike chess, there are extra board features such as the river (河 - hé) and the palace (宫 - gōng), and these influence how a player can move their pieces. There are also rules against perpetually repeating the same move. For a more detailed description check out this video or this website.

Now you've been equipped with the fundamentals, all that's left is to head to a park (gōngyuán - 公园) and play. Grab a table (zhuōzi - 桌子), a batch of sunflower seeds (guāzǐ - 瓜子), a cup of green tea (yībēi lǜchá - 一杯绿茶) and some friends (péngyǒumen - 朋友们) and begin your classic Chinese game odyssey!