Learning Mandarin: Unpacking Chinese Names for World Countries

Not only do country names teach us new vocabulary and expressions, but they also provide insight into China's history and global perspectives.

A great starting point if you want to learn Mandarin is through Chinese country names. The myriad names for the nations of the world can initially seem a little daunting to a new Mandarin learner, but fear not! This blog will break down the nomenclature related to a selection of country names, along with providing some intriguing facts.

The names that China has given to foreign lands can not only help you learn new vocabulary but can also shed light on how China has internationally perceived itself and others. One of the first interactions you'll likely have with a Mandarin speaker is explaining where you come from. When you hear the immortal words, “你是哪个国家的” nǐ shì nǎge guójiā de ("what country are you from?"), this article should give you the ammo to sufficiently respond.

What is The View From the Middle Kingdom?

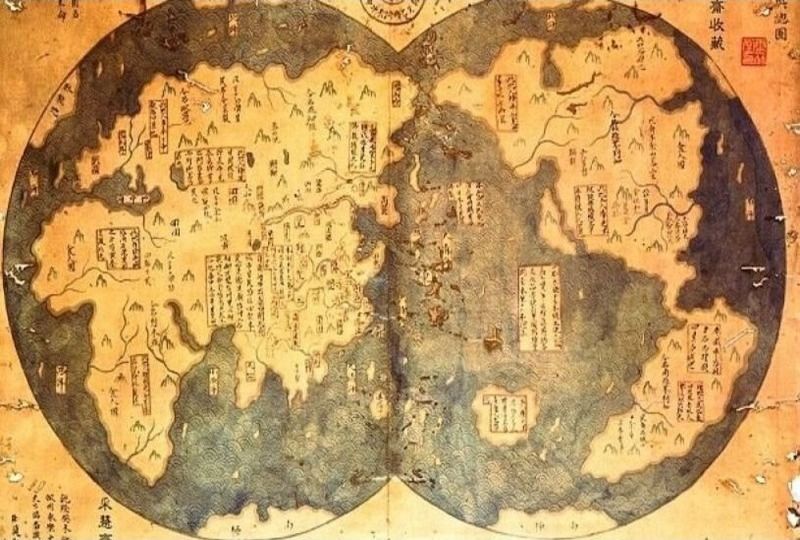

Where better to begin than with China itself? 中国 - zhōngguó, literally translates to Middle Kingdom, emphasizing China's historical belief of being at the center of the world. As seen on old maps, China was often placed squarely in the middle, with nations outside of its borders often skewed and superfluous (many countries were guilty of this!). The concept of "tiānxià" 天下 ("under heaven") gave license to this world-view and has since shaped much of China's outlook in regards to global perception. With the "Mandate of Heaven" bestowed upon its land, of course China must be at the center of the world.

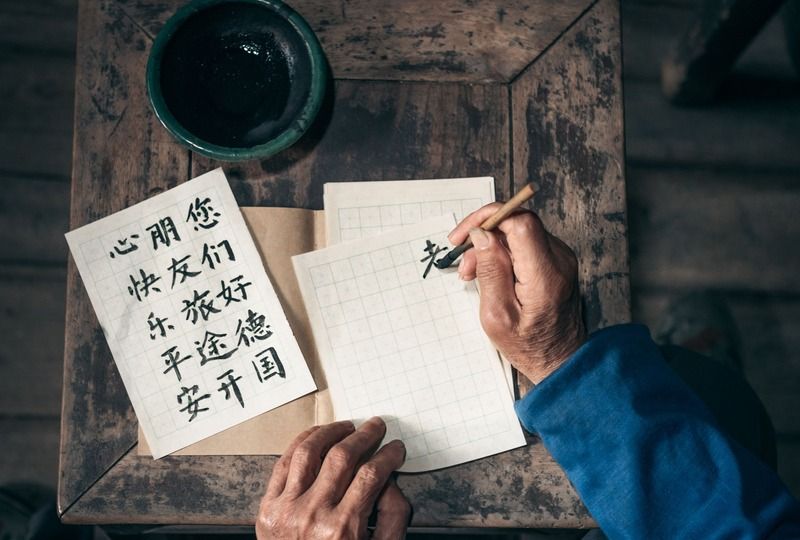

While it's difficult to provide precise explanations for how country names were devised (dynastic cycles/multiple revolutions meant a lot of instability and changes in external outlook), it's evident that the earlier-assigned names typically combined the word 国 guó (country) with a relevant homophone (a word sharing in pronunciation with other words but with a different meaning). These countries were generally kingdoms that China had historical dealings with, either through early trading routes or burgeoning European colonial influence. Here are some examples:

- United Kingdom: 英国 - yīnɡɡuó ("brave" or "hero" country)

- France: 法国 - fǎguó ("law" country)

- Germany: 德国 - déguó (country of "morality")

- Thailand: 泰国 - tàiguó ("peaceful" country)

- United States: 美国 - měiɡuó (“beautiful" country)

While these somewhat flattering names could arguably seem at odds with the current, harsher realities of these places, the majority will have been assigned vernacular that appealed to the Classical Chinese ear, combined with a phonetically similar sound—for example, "Ying"("Eng") or "De"("Deutsche").

Decoding the Art of Chinese Transliteration for Foreign Country Names

How about nations such as another early trading partner, Holland 荷兰 hélán, that don't employ the suffix guó? The Chinese language has a relatively small stock of sounds compared with English. In fact, there are only around four hundred syllables in Chinese, which contributes to the creation of some rather rough transliterations.

The simplest transliterations are romanized country names that share similar phonetics with those already existing within the Chinese stock (usually broken down by syllable). If there can also be a fitting meaning attributed to the name, then that's a bonus. However, often, the name is simply the closest transliteration, without emphasis on meaning.

1. "Clean" Transliterations

- Finland: 芬兰, fēnlán

- Djibouti 吉布提 jíbùtí

- Philippines: 菲律賓 fēilǜbīn

- Kenya: 肯尼亚 kěnníyà

- Mali: 马里 mǎlǐ

- Italy: 意大利 yìdàlì

- Norway: 挪威 nuówēi

- Haiti: 海地 hǎidì

There are dozens more names that follow this format; however, when the existing syllable sound does not match with those in the Chinese vernacular, we end up with an interesting melange of linguistic east meets west.

When the name starts with R, V, or U, when a T appears in the middle of the word, or when a portion of the name is simply missing from the Chinese, it can result in instances of this mixing. This can also occur when combinations of "st" or "th" are present, among other scenarios.

2. "Fuzzy" Transliterations

- Mexico: 墨西哥 mòxīgē

- Portugal: 葡萄牙 pútáoyá

- Vanuatu:瓦努阿图 wǎnǔātú

- Turkey: 土耳其 tǔ'ěrqí

- Australia: 澳大利亚, àodàlìyǎ

- Romania: 罗马尼亚 luómǎníyà

- Rwanda: 卢旺达 lúwàngdá

- Ukraine: 乌克兰 wūkèlán

The notion that the ancient Chinese saw Mexicans as their western ink-brothers (墨 mò - ink, 西 xī - west, 哥 ɡē - elder brother) or the Portuguese as grape-toothed (葡萄 pútáo - grape, 牙 yá - tooth) is amusing, but it's more likely that these were just the best phonetic matches available!

While we can still determine which countries these "fuzzy" transliterations could be based on their sound combinations, there's another set of nations that would prove difficult to identify without at least a passing familiarity with Mandarin; we'll get to those later.

Imperial China’s Lingual Influence on Neighboring Nations

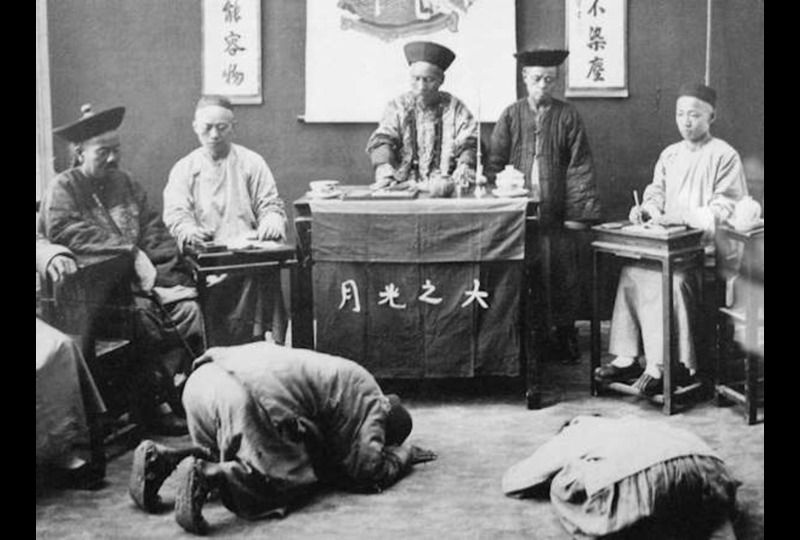

At various points in history, China's surrounding countries adopted the written and legal systems that China had already developed, and they acknowledged the importance of the Middle Kingdom by partially employing the Chinese language.

This stemmed from multiple relationships of trade, military force, diplomacy, and ritual dating back to the Han Dynasty. To partake in the "Tributary System" 中华朝贡体系 zhōnghuá cháogòng tǐxì (commonly known as the "Kowtow" system), other kingdoms sent a tributary envoy to China to show their deference, and whilst never officially part of China, these nations were historically under the loose grip of China's imperial structure and China's "Mandate of Heaven" (天命 tiānmìng).

Japan 日本 rìběn and Korea 朝鲜半岛 cháoxian bàndao (“Korean Peninsular") are two prominent examples. Following Korea's division, North Korea continued to be known as 朝鲜 cháoxiǎn, but with the addition of "北" běi (north), becoming 北朝鲜 běi cháoxiǎn. South Korea is nowadays commonly referred to as "韩国" "hánguó".

In keeping with the Western moniker "The Land of the Rising Sun", Imperial China thought it appropriate that as the eastern perimeter of the world, Japan should logically be known as 日本 rìběn, literally meaning "sun origin." The current Japanese name for Japan, "Nippon," has reflected this etymology since the Chinese introduced Hanzi to the archipelago (which developed into the Kanji script that remains today).

On a similar note to Japan's "original sun," the literal translation of 朝鲜 - cháoxiǎn is "fresh dawn", again potentially alluding to Korea's eastern geography. Conveniently, cháoxiǎn also holds a similar sound to Joseon, the official name for unified Korea until the country was annexed by Japan in the 19th century. The name was denoted as a tribute to the Ming, who were ruling China at the inception of the Joeson Kingdom at the end of the previously ruling Goryeo 高丽 gāolí.

Vietnam, 越南 yuènán, is another intriguing example. The character “南“ nán represents the south, while 越 yuè refers to China's southern kingdom dating back to the Zhou Dynasty. 越南 yuènán therefore denotes Vietnam as the "land south of the Yue", again illustrating China's regional supremacy during a period when Vietnamese borders with China were perhaps more permeable.

Literal Translations: Keeping Chinese Names Simple?

Sometimes, we just have to call a spade a spade. Clever transliterations and cute names denoting geography or cultural factors are occasionally thrown out of the window. The following exemplifies some clean examples of literal, non-phonetic translations with minimal alterations.

- Iceland: 冰岛 bīngdǎo ("Ice Land")

- Montenegro: 黑山 hēishān ("Black Mountain")

- South Africa: 南非 nánfēi ("South Africa")

Another interesting example is Belarus 白俄罗斯 bái'éluósī, which, in its romanized form, literally means "White Russia". The Chinese translation maintained this with bái 白 (white) and éluósī 俄罗斯 (Russia) and managed to loosely capture the original phonetics.

Other non-phonetic examples are Switzerland 瑞士, ruìshì ("lucky scholar"), Sweden 瑞典 ruìdiǎn(“lucky law"), and Greece 希腊 xīlà ("hopeful of the 12th month").

Name the World: Useful Phrases to Introduce Yourself in Chinese

China usually uses descriptive translations or phonetic transliterations to name overseas territories in an effort to mimic the sounds or features of the original countries. Geographical, cultural, and historical elements are frequently reflected in these names. But logic and reason are not always applied, so we may presume that the people who were tasked with selecting these names were either amusing themselves or that a more arbitrary explanation was at play!

Now that you've been equipped with some knowledge on how China has named the world, all that's left is for you to go and introduce yourself!

你从哪里来?nǐ cóng nǎlǐ lái? (Where do you come from?)

你是哪个国家的? nǐ shì nǎge guójiā de? (What is your home country?)

你是哪国人? nǐ shì nǎ guó rén? (What is you nationality?)

我是英国人!wǒ shì yīngguó rén. (I am English)

我去过二十三个国家 wǒ qùguò èrshísān gè guójiā! (I've visited 23 countries!)