The 4 Best Ways to Learn Kanji for Japanese Learners

'The truth is that there is no one-size-fits-all method for studying kanji. The best way to learn depends on your Japanese-learning goals.'

Learning kanji is an integral part of learning Japanese - and possibly the most interesting. The more you learn, the more you start seeing connections between characters, their components, meanings and readings, which is incredibly rewarding.

However, studying kanji is undeniably a long road, and choosing the right path to take can be tough.

How to Find the Right Kanji-Learning Method for You

People have come up with a lot of different frameworks for studying kanji:

RTK, Kodansha Kanji Learner’s Course, JLPT levels, the jouyou kanji by school grade. Trying to decide between all of these, you might feel a bit lost before you even start learning!

If you're feeling overwhelmed with all the different methods for learning kanji, I'm here to help! The truth is that there is no one-size-fits-all method for studying kanji. The best way to learn depends on your Japanese-learning goals.

With that in mind, I will briefly introduce the different ways to study kanji and consider their pros and cons in this article. At the end of it, you will hopefully be more confident to choose your own kanji-learning path!

Making Sense of Kanji-learning Methods

1. Remembering the Kanji: A Foundational Work With Limited Practical Use

Remembering the Kanji, often abbreviated to RTK, is considered a seminal book in the world of kanji-learning. Authored by James W. Heisig, its first volume was published in 1977; two sequels and numerous new editions have since followed.

The RTK approach to learning kanji is divisive. Some people say it’s a great foundation for long-term studies of Japanese, while others argue it’s deeply flawed.

In the first volume, Heisig focuses exclusively on familiarising learners with the meanings of individual kanji and omits their readings completely. Kanji are introduced together with ‘stories’ that are supposed to tie the character’s form to its meaning. It’s only in the second volume that Heisig begins teaching the readings of characters as well - this time, without any ‘stories’, only one reading and one example word.

Overall, I find the method of teaching the meaning and the reading of kanji in isolation to be less effective than teaching them in combination. Learning kanji without knowing how to pronounce them is not very useful, if your goal is reaching practical fluency in Japanese.

Moreover, the method of teaching readings in the second RTK volume is not effective, because the kanji are not taught in context. One kanji can have a vast amount of different readings - without seeing various examples of the kanji being used as part of words and sentences, it is simply not possible to really ‘know’ it.

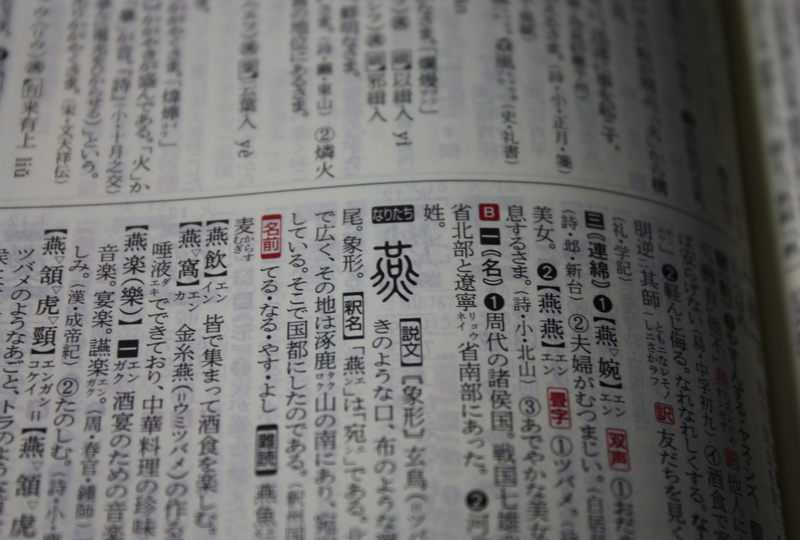

Another problem I have with RTK is its use of ‘elements’ instead of standard radicals. In Japanese, the components that make up a kanji are called ‘radicals’ (部首 ‘bushu’). Deriving from the Chinese Kangxi dictionary, there exists a standardised list of 214 radicals in Japanese.

Instead of using these standard radicals, however, Heisig chooses to come up with his own way of classifying kanji components as ‘primitive elements’. His elements often align with the radicals, but not always, and their Japanese readings are not given. This can be problematic, because familiarity with the 214 radicals is a great learning aid, particularly when you progress to a more advanced level of kanji-learning.

The verdict:

Probably the most divisive method for learning the kanji, the RTK has its fans and its critics. It makes its own rules that sometimes seem arbitrary.

The main purpose of using the RTK is becoming familiar with kanji, not becoming functional in their usage; if you’re interested in entering the world of kanji for the first time, the RTK may be a fascinating foundational book with its mnemonic stories. However, it will teach you fewer practical skills than the other resources on this list.

2. Kodansha Kanji Learner’s Course

Kodansha Kanji Learner’s Course, often abbreviated to KKLC, is the other big book-based method of learning kanji. It takes an approach that is much closer to how Japanese people learn kanji at school. As outlined in the introduction, this method is designed to be as pedagogically sound and comprehensive as possible.

Learners will be introduced to a kanji, its radical, its onyomi and kunyomi readings as well as a short mnemonic description and several example words simultaneously. In this way, the KKLC enables learners to gain functional kanji-reading skills faster than the RTK. There is also an additional Kodansha Kanji Learner’s Dictionary which offers more in-depth information on the kanji; it’s highly recommended to use this in conjunction with the KKLC.

KKLC covers all of the 2136 jouyou kanji and some other useful kanji. Instead of using the school grade sequence common in many other kanji textbooks, the author has chosen to group kanji that are graphically similar together. Some learners may feel this is an effective way to understand connections between kanji that share radicals, while others might find it confusing to learn groups of similar kanji. This is one of the most divisive things about the KKLC.

The verdict:

The KKLC is a more balanced and pragmatic introduction to kanji than the RTK. Its grouping of kanji by graphical similarities, instead of school grade or frequency, may be a pro or a con depending on your viewpoint. Presenting a more pedagogically ‘scientific’ and modern approach to learning, the KKLC is an effective way to get to grips with kanji.

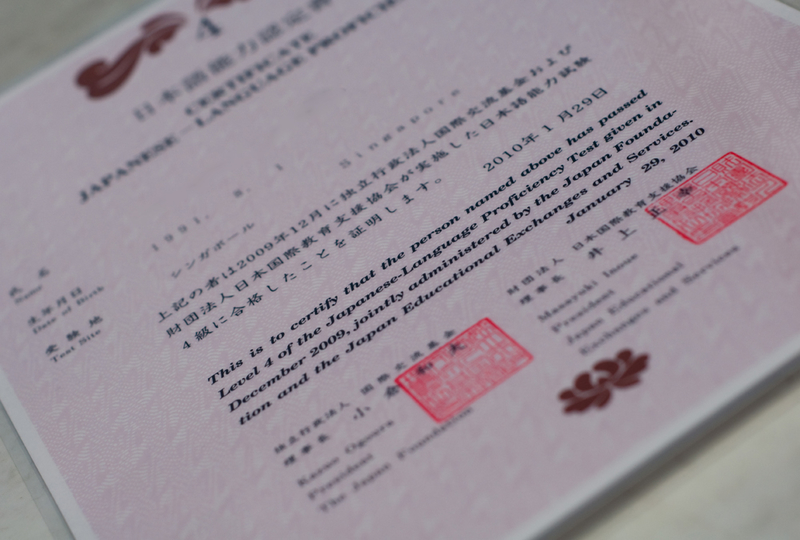

3. JLPT Levels

This is not a specific learning resource but rather a framework of learning kanji for one specific purpose: passing the internationally recognised JLPT (Japanese Language Proficiency Test). The JLPT is a bit like the TOEFL of Japanese - schools and employers often want applicants to have a specific level, so passing it can have many practical benefits. However, the Japan Foundation isn’t very forthcoming on the specific content of each ‘level’, and no official kanji lists for each JLPT level have been published.

However, there exists a consensus on which kanji usually pops up on which level, and you can get workbooks and webpages designed to help prospective exam-takers ace everything from the N5 to the N1.

You can probably guess what the verdict is on this one. If you want to pass the JLPT, cramming kanji by JLPT level is a good idea - otherwise, it might not be the ideal way to learn. Personally, I’ve studied kanji using other methods in the long term and resorted to revising JLPT kanji workbooks a couple of months before taking the exam with good results, so this is a strategy I could recommend. Of course, the same applies to other kanji tests such as the 'hard mode' Kanji Kentei.

4. Jouyou Kanji by School Grade

The jouyou kanji (常用漢字), literally ‘regular-use kanji’, is an official list published by the Japanese Ministry of Education. The latest 2010 list contains 2136 kanji and forms the backbone of the Japanese kanji curriculum throughout primary and secondary school.

Of course, the jouyou kanji list isn’t everything there is to learning kanji - many more are needed to read literature or academic journals, and a few common characters are actually omitted from the list. But mastering these kanji is definitely a strong foundation for achieving comprehensive Japanese skills. By learning the jouyou kanji, you’ll essentially be at the same level of reading ability as a 15-year-old Japanese teenager, which is not too bad!

The jouyou kanji list forms the basis of many other kanji learning resources, such as the KKLC, although the sequence of characters doesn’t always follow the school grades. However, if you’re looking for a good ‘traditional’ way of learning kanji, just following the school grade lists is not a bad idea.

You’ll be able to trace your progress naturally and find extra reading materials more easily - for example, after completing the 3rd grade jouyou kanji, you’ll know you should look for children’s manga or books targeted at that age group. Like I said in the beginning of this article, there is no ‘one size fits all’ way of learning kanji, but this is how all Japanese kids learn their kanji, so it’s probably the closest to such a model.

The Final Verdict

The method you should use to study kanji completely depends on what your goals are.

-

If you're a complete beginner fascinated by kanji, RTK offers a way to gently familiarise yourself with them.

-

If you want to use a more 'scientific' way to become functional fast, the KKLC is designed to be as pragmatic as possible.

-

If you want to get a new JLPT level under your belt, using resources designed for that is a good idea.

-

If you want to take a more 'middle-of-the-road' approach and learn the way Japanese children do, studying the jouyou kanji by school grade makes sense.

Therefore, all you need to ask yourself is - what's your kanji-learning goal?

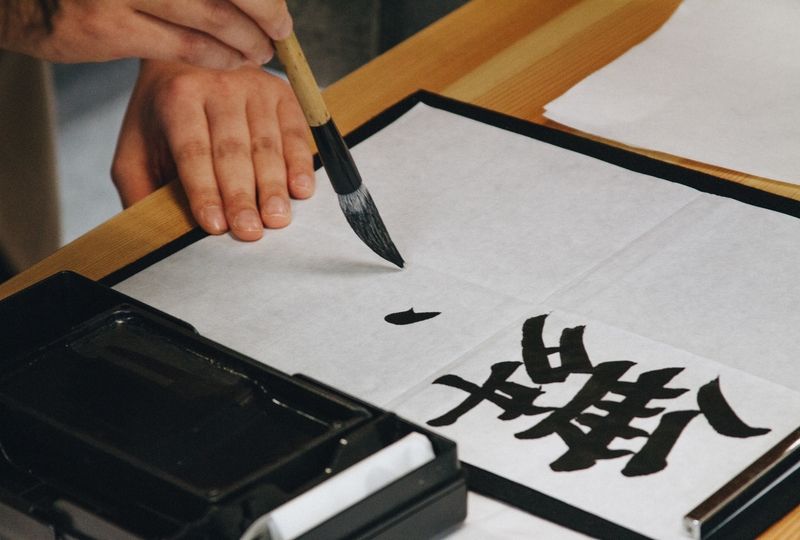

No matter which method you choose, the very basics of studying kanji are always the same. Learning and recognising kanji in context is a great idea, as is writing characters down by hand (or in an app) to get them in your muscle memory, so to speak! For more practical advice on memorising kanji, have a look at this post on learning hanzi - these tips are applicable to Japanese as well!

Whichever method of learning kanji you choose, you’ll see it only gets more interesting as you go along!